The Archaeology Fund

MSAL: Who Are These People

|

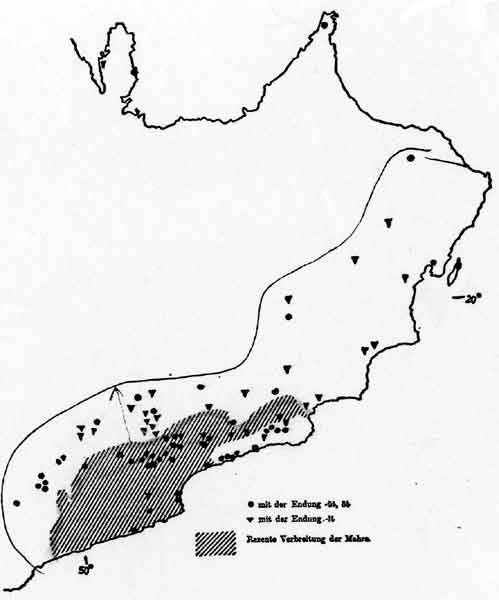

In 1834, a young man stepped aboard a British ship anchored off Jedda speaking in an unrecognizable language, and so began the western investigation into what became known as the Modern South Arabic languages. By the turn of the twentieth century, scholars had realized that a distinctive set of languages and cultures were present in south central Arabia which were Semitic, but classed as non-Arabic. These languages were identified with tribal groups and labelled as Mahra, Shahra/Jibbali, Hobyot, Harsusi and Socotri DH1-112]. All except the Harsusi are to be found within the present distribution of Incense country. The ethnographic features of their languages and cultures are just beginning to be detailed DH1-044, DH2-037, DH1-118, DH1-119], but it appears that one of the "mysteries" of research involves the relationship between these Modern South Arabic Language (MSAL) speakers and the archaeological-historic past [DH2-026]. By the late 1950's, both ethnographers and linguists had suggested that from at least eleventh century AD, period, their past range as tribal groups was much larger than at present DH1-116]. Furthermore, the famous Khor Rohri gate inscription, which mentions the land of SKHLN, has been identified as the Sachalites [IC-055, PS-020, IC-056] described in the Pliny classical period text. B. Thomas by 1929 was one of the first to note that several of the local Shahra groups in the Salalah region referred to themselves as the Hakalai which modern linguists equate with the South Arabic term Sakalan. Thus, this term may have been one of the tribal groups of the ancient MSAL in the Salalah region at the time of Pliny and Ptolemy. Similarly, the term Mahra has been projected into the early Islamic period (seventh-eighth centuries AD) by historians such as al-Tabari. Several authorities have also suggested that the term Mahra can be found in ancient South Arabic texts of the late centuries B.C. We have also noted that the early alphabetic script was used in the South Arabian region by the Late Iron Age [DH1-060, DH1-110, DH1-124] and translations of these undeciphered texts may shed light on the contemporary peoples of the area Such texts may also help us understand the meaning of the mysterious and contemporary triliths (see above). Finally, in this regard, if we take the early Islamic distribution of the MSAL speakers and overlay our knowledge concerning the trilith distribution [DH2-042], we could be tempted to suggest that the Iron Age peoples [DH1-049, DH1-046, DH1-082, DH1-111] of the region were the ancestors of the distinctive modern MSAL groups. |

|