The Archaeology Fund

Iron Age

|

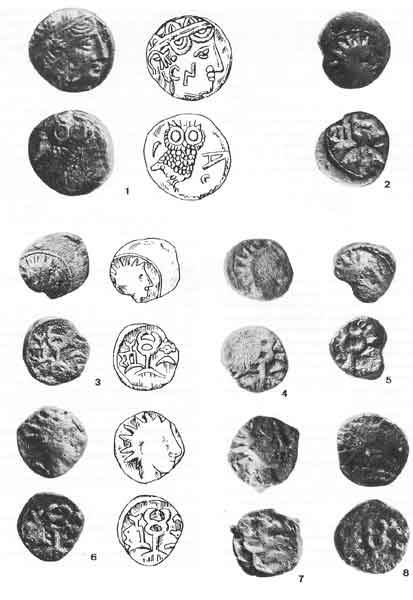

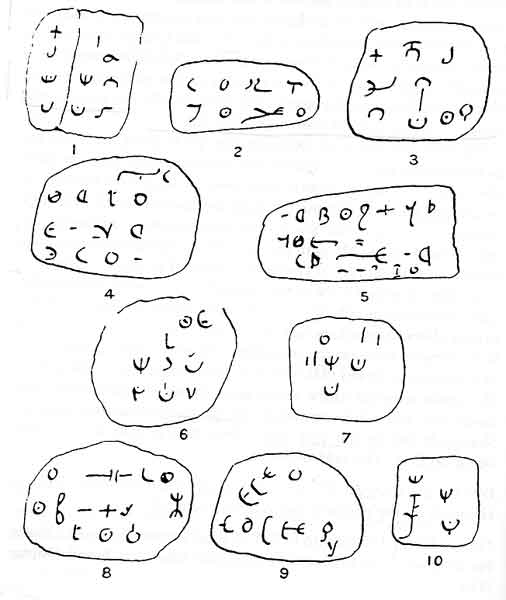

The defining focus for the Iron Age period of southern Arabian revolves around the creation of the classical South Arabian city states. Deep soundings at Hajar Bin Humeid already in the 1950's suggested that the formal city states had already originated by the turn of the late second millennium B.C. Subsequent work at Shabwa, Yalah, the Marib area and elsewhere confirmed this supposition. Large scale towns developed in relationship to the creation of sophisticated seil irrigation controlling agricultural water into the interior Ramlat Sabatayn basin. (Use Marib USGS LANDSAT 7). Such urban centers also developed literacy perhaps due to direct or indirect contacts with the Levant far to the north. The Queen of Sheba accounts in the Old Testament may have some legitimacy based on such contacts and or trade relations developed in the late second and early first millennia B.C. These accounts may be supported by references to "Queens of the Arabs" in early first millennium B.C. Neo-Assyrian sources from Nineveh (see Ephal, The Ancient Arabs). The ancient land trade routes along the spine of Arabia were already in place by the Bronze Age (see above) but intensified during the succeeding Iron Age. Sea trade was also highly developed during the preceding Bronze Age (link) and continued to flourish in the Iron Age period. (The Biblical term "Ophir" in the book of Kings refers to the subject known as "King Solomon's Mines" and should be sought in west-central Saudi Arabia, "Mahd ad Dhahab"). To the northeast, modern UAE/Oman was closely tied to the Persians as evidenced by lithic and ceramic material found at a number of sites. Archaeological work in Southern Arabia has yet to cast light on this early Iron Age period, perhaps with the exception of the recovery of flint microlith production at a number of sites. Such microliths in western Yemen in the Wadi Jowf have been dated to the early centuries B.C. Excavations at such Iron Age sites as Taqa 60 and Hagif, may yet push our dates back into the early first millennium B.C. as well. To date, our surveyed and excavated material may date back to the mid-first millennium B.C. By the later Iron Age, the South Arabian city states began to increasingly come into contact with first the Greek city states and later the Roman Republic/Empire. Both material remains such as ceramics, coins, and statuary as well as historical sources testify to strong and vibrant relationships. To the east, the Achaemenid Empire describes its control of Maka, a province in northern Oman/UAE. Shabwa, as the capital of the Hadramaut, desired to control the incense lands directly and so established a fortified colony at Khor Rohri (ancient SHRM), Greek Moscha. The Anonymous Merchant of the Periplus (ca. 100 AD), Pliny (79 A.D.) and later Ptolemy (150 A.D.) all describe our region of incense production in relationship to the lands both to the west and east. Thus, the number of sites in southern Arabia perhaps contemporary to the colony at Khor Rohri grew dramatically as defined by settlements, tombs, lithics and ceramics. To what extent the modern populations of the region [see MSAL mystery] represent the descendants of the Iron Age peoples remains to be worked out in detail. By the advent of the first centuries AD, we can plot a number of variables for the region including tribal names, and textual site locations matching archaeological sites. The Iobaritae, probably modern Habarut, for example, noted on Ptolemy's map, may be a reference to the Ubarites and the later "Ubar " of Islamic story fame (see link). Excavations at such interior forts as Shisur may date to this period and suggest incense traffic both across the southern interior of the Rub al Khali as well as caravan trade westward following interior wells. The presence of the mysterious triliths may be part of this incense trade (see link). Rock art and inscriptional material have been recorded at a number of sites both from triliths, boulders, rock walls, and cave interiors. Their link to other Arabian groups to the north appears greater than to the classic south Arabian city states to the west. Ceramic material from our region dated as late as ca. 550 A.D. also suggests closer links to Oman including Sohar reinforcing the suggestion by classic authors that incense producing lands lay closer to Persian influence. Be that as it may, a number of complex factors including Christian conversion, climate change, and socio-political control of the South Arabian city states finally led to a serious decline in the incense trade by the advent of Islam. |

|