The Archaeology Fund

Islamic Period

|

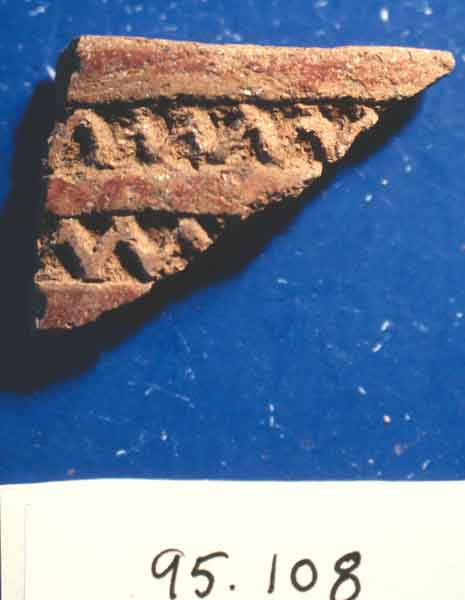

The Late Classical occupation of the sixth and seventh centuries AD of South Arabia have been documented on previous pages. It stands to reason that the Islamic conversion of the mid seventh century involved the same people. We are aware of these tribal groups principally through the reports of Al-Tabari. Subsequent Islamic historians such as Yaqut, Al-Idrisi, Al-Istakhri and Ibn-Khaldun accurately depict the geography, landscape and tribal groups of the region, principally known as Al-Akhaf. Archaeologically, our recovered sites fit into the larger chronological scheme proposed for the Islamic Period by Whitcomb and others into the commonly accepted tripartite arrangement. This chronology binds together both archaeological materials reflecting Arab empires as well as local sequences from South Arabia. For example, Early Islamic sites such as Jebel Qinqari and Khor Rohri are defined on the basis of Iraqi Abbasid wares of the eighth and ninth centuries AD. Later Islamic periods include the presence of Fatamid Lusterwares, Sgraffiato, underglazing, and Turkish greenwares. Locally our excavations in the Wadi Masilah revealed a continuous occupational sequence from the ninth to the nineteenth centuries as revealed by carbon fourteen dates and primarily local Islamic wares. We have therefore been able to isolate such interesting ceramics as Socotra polished blackwares to the Early Islamic period. The "Ubar" mystery as created by later romantic Islamic stories such as "The Thousand and One Nights" (see link) has a definite historical underpinning as described by both classical and Islamic historians. Such accounts undoubtedly have their origin in the thriving incense trade which bridged both the Late Classical and Islamic worlds. Both historical and archaeological data generally point to a continued thriving incense trade over not only the Arabian Peninsula but also as a link between East Africa, India and China. This Northern Indian Ocean trade was not to collapse until the arrival of the Portuguese and the Ottoman-Turks. To what extent climactic deterioration played a role in its demise remains elusive. The modern tribal groups which make up the MSAL classification (see link) are therefore a visible link to a long and distinguished historical and archaeological past. It remains for future researchers in the fields of biology, botany, linguistics, history and archaeology to shed light on this fascinating corner of the Northern Indian Ocean. |

|